CUBA'S CAPONES

Top Dogs in Batista's

Casinos

[REF:

UNTOLD STORY: FIDEL CASTRO, Vol 1 No. 2, September 1960

p28]

[MEMO FROM THE PUBLISHER

The Editors of this magazine have tried to present all sides

of Castro,

the man, the rebel, the conqueror. We were impressed with

his

philosophy of reform, not so impressed with his carrying-out

of

justice. We have grave misgivings concerning his

reputed alliances

with Russia. But we feel that each reader must get the

whole picture

for himself before making any personal judgment. And

here it is, for

the first time, the whole UNTOLD STORY of Cuba's Fidel

Castro.]

CUBA'S CAPONES

Top dogs in Batista's

casinos were the Syndicate

boys from the United

States–the ones who'd been

lucky enough to stay alive

during Capone's era.

[To

see a full size photo, right click and VIEW IMAGE]

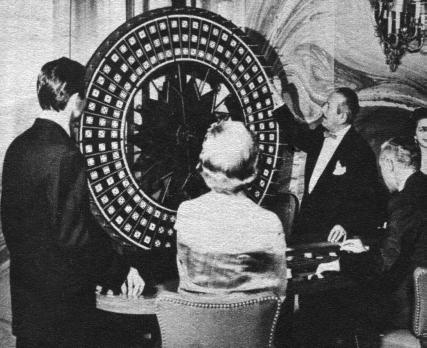

Gambling was a multi-million dollar industry --

the play ran over a million a night with no bet limits.

[To

see a full size photo, right click and VIEW IMAGE]

HAVANA went berserk on New Year's Day, 1959. Wild-eyed

young men

and women erupted from their homes into the streets.

Students

poured out of the campuses. Instead of recuperating

quietly from

the revels of New Year's Eve, Havanans flocked outdoors in

droves.

They cheered, they whistled, they danced in the streets when

they heard

that Batista, his family and cohorts had fled the country by

plane at

about two a.m.

The people surged toward downtown Havana. They carried

Cuban

flags and sang the national anthem. Car caravans

bedecked with

flags, the horns blowing, inched through the marchers.

In downtown Havana, the crowds reached a peak of excitement,

then raced

for the luxury hotels which housed the biggest gambling

casinos.

The casinos were prime targets of Castro. They were

run by

professional gamblers and gangsters from the United States

who had paid

the Batista regime huge sums for the privilege.

Batista's brother-in-law controlled all 10,000 slot machines

in Cuba,

which contributed million to the regime's bank

account. The slot

machines, symbols of the ousted leader, were especially

sought out by

the mobs.

Most of the demonstrators had never been able to afford the

high-priced

pleasures of the multi-million-dollar hotels. Now they

didn't

hesitate. With a roar they shoved their way into the

air-conditioned, deeply carpeted hotel lobbies and made for

the casinos.

The demonstrators were not there to place bets, but to wipe

out the

citadels of the corrupt and privileged classes. In the

huge

lobbies of the hotels, they finally found the doors to the

casinos–and

found them closed.

Rifle butts, clubs and lobby furniture pounded against the

solid doors

until the bars and locks gave way. Inside they found

roulette

tables, dice tables and card tables, hundreds of thousands

of dollars

worth of gambling equipment in each casino. There were

fancy bars

with every kind of liquor available. On the floors

were deep-pile

carpets and overhead sparkled costly chandeliers.

With howls of revenge the mob set to work destroying the

playthings of

the rich. The slot machines were overturned and bashed

into

twisted hulks of metal. The roulette wheels and tables

were

broken into more parts than they had numbers.

The military and the police had wisely stayed in their

barracks.

The officers knew that their men would encourage and perhaps

join the

mobs. There was nothing and no one to prevent the

crowds from

taking the casinos apart from wall to wall. They

did.

Nothing was left usable or in one piece.

By the end of New Year's Day, there wasn't even a matched

pair of dice left in the casinos of Havana.

Fidel Castro had always hated gambling. He viewed it

as a

criminal waste of the nation's financial resources and, as

during the

heyday of Fulgencio Batista, as an invitation to

governmental graft and

corruption.

When Castro finally gained power in Cuba, he abolished

gambling in his

first batch of decrees. Then he learned the facts of

government

life–it was a losing bet to attempt running the country

without the

gambling revenue. Without the spinning wheel and the

click of the

bones, tourists would go elsewhere.

Thus, he legalized it again, just as the others before him

had, but he

added a new twist. The gambling is run under strict

supervision

of the government, and Castro has promised that any official

found

dipping his hand into the till will be punished most

severely.

None has been caught yet.

Two types of gambling predominated in the days before

Castro.

Both held opportunities for graft. There were the

games of

chances played in casinos, and the lottery run by the state.

The plush casinos and gambling houses in Cuba during the era

of Batista

were run by some of the Syndicate boys from the United

States, the ones

who had been smart or lucky enough to escape death as

gangsters during

the Capone years in Chicago.

The Syndicate boys were the only ones who knew enough to run

the

casinos at a profit. They were the best in their

business and

were considered respectable businessmen in Havana.

Instead of

using guns for protection, they paid government officials

for the right

to operate without trouble. It cost fantastic sums to

operate and

pay the government officials and taxes and still come out

with a

profit, but the gangsters had spent a lifetime learning

their trade and

proved in Cuba that they had graduate with honors.

Top dog in the legitimate

gambling racket in Cuba was

Meyer Lansky,

known in the United States as the man whom Senator Kefauver

and

committee had dubbed as one of the top ten racketeers in

this

country. Lansky knew all the angles and he was very

happy when

Batista asked him to come out into the sunlight of

respectability and

set up the legalized gambling venture in Cuba.

Lansky brought to Cuba the cream of the gamblers from Las

Vegas, Reno,

and New York. His right-hand man was his brother Jake,

who was

installed as floor manager in the Hotel Nacional's

casino. Then

there was

Santo (Louis Santos) Trafficante

Santo (Louis Santos) Trafficante from

Florida, the Einstein

of the numbers game. Trafficante was given a

full interest

in the casino of the

Sans Souci Hotel

Sans Souci Hotel,

with other big slices of the

gambling pies in the Comodoro and

Capri Hotels

Capri Hotels. Joseph

(Joe Rivers)

Silesi managed the business for Trafficante.

Actor George Raft

Actor George Raft

also bought a piece of the Capri.

There were others, too, floating around in the thick, rich

gambling

gravy of Cuba. Fat the Butch from New York's

Westchester County

presided over the dice tables in the Capri. Thomas

Jefferson

McGinty of Cleveland's underworld brought his special

talents to the

Nacional.

"Honesty is the best policy" was the slogan of these hoods

in

Cuba. They had learned that more money is made faster

when their

enterprises had good public relations. They donned

conservative,

made-to-order suits, white shirts and ties, and cleaned up

their

grammar. With government charters, there was no need

for gangland

slayings a la Capone to bump off the opposition – because

there was no

opposition.

The tourists and well-heeled Cuban customers in the casinos

had no need

to worry about loaded dice, stacked decks or a fixed

roulette

wheel. The theory of mathematical probability and the

laws of

chance assured the house of winning.

So the racketeers kept it clean...to the point of hustling

out of

their fancy dens any slick operators who wanted to fleece

the customers

with unchartered methods. When word of this reached

the United

States via Madison Avenue, the gambling boom was on in Cuba.

When the American tourist reached Havana after a five-hour

flight from

New York, he had a choice of about five multi-million-dollar

swank

hotels. There were also numerous nightclubs in Havana

which had

facilities for gambling. All were million-dollar-plus

establishment – Batista had changed the gambling laws in

1955 to allow

gambling rooms in any club or hotel worth a million.

His

government also helped finance the buildings and put up

millions to

help with construction. Import duties were waived on

materials

for hotel construction and Cuban contractors with the right

"in" made

windfalls by importing much more than was needed and selling

the

surplus to others for hefty profits.

These schemes were what had aroused the wrath of Castro and

the

citizens of Cuba. They saw their government

giving money

with little return expected; what should have been returned

to the

government coffers with interest went to line the pockets of

corrupt

officials.

The government was to get $25,000 for license plus twenty

percent of

the profits from each casino. What Batista and the "in

group" got

has never been certified. It was rumored that to get a

license a

fee for $250,000 and sometimes more was required under the

table.

Periodic payoffs were requested and received by the corrupt

politicians.

The slot machines in Cuba, even the ones which dispensed

small prizes

for children at country fairs, were the province of Roberto

Fernandez y

Miranda, Army general, government sports director and

Batista's

brother-in-law, Roberto, was also given the parking meters

in Havana as

a little something extra. Parking meters didn't fare

too well

when the rebels first came to town.

Cubans had never been trained for gambling operations on

such a large

scale, so pit bosses, dealers and stickmen were brought from

the United

States as "technicians," and in that category were allowed

to stay on

two-years visas. These men, veterans of the "working

class" of

illicit U.S. gambling, eventually turned into "teachers" for

the

Cubans. Their teaching certificates are on record in

police

blotters, courts and prisons throughout this country.

Now that Castro allows only Cubans to act as croupiers, the

Americans

stand by and tell the "students" what to do. Someday

soon, Cuba

will have its own sizable working class of gamblers.

The second major type of gambling in Cuba was the national

lottery

which had been started sometime in the dim past and reached

its finest

flower under Batista. The drawings in the lottery had

been only

once a week, but under Batista they were increased to a

daily

institution. Every night, all Cuba stopped activity at

9:30 to

listen to the radio, which punctually listed the winning

numbers.

Government printing offices were kept busy printing the

tickets and

astrologers and swamis flourished in picking lucky numbers

for their

superstitious clients.

Unofficial lotteries, called bolitas, were also encouraged

by

Batista. These tickets carried the same numbers as the

official

ones and paid off on the officially drawn numbers.

The police forces in Cuba, with moral codes which would

shock the most

corrupt cop in the U.S., shook down the bolita operators for

as much as

they could get. It increased their incomes

tremendously, which

created great loyalty to Batista.

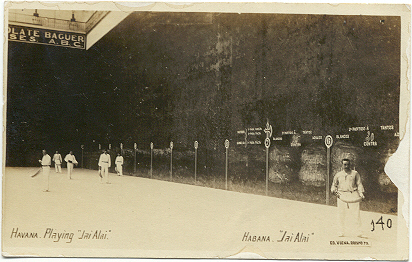

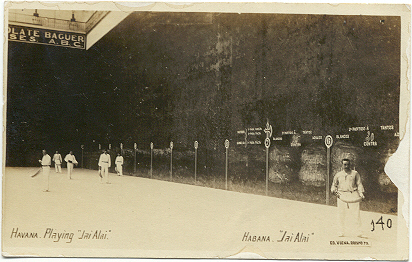

On the margin of Cuban gambling activity were the bloody

afternoon

cockfights, the nightly

jai-alai

jai-alai contests,

and the

horse-racing

horse-racing

tracks. The tracks allowed many more betting

combinations than

those in the United States, including a Cuban form of

numbers betting,

different daily doubles and parlays. If this confused

the

tourist, he could always duck into the casinos at the tracks

for more

familiar types of betting.

This many-tentacled gambling octopus was what confronted

Fidel Castro

on his assumption of power. His strict moral sense

condemned it

all and, true to his pledge, he abolished it with a

proclamation.

Then his troubles began.

There in the heart of Havana, towering over the shores of

the

Caribbean, reflecting the sun and moonlight in the clear

air, stood

millions upon millions of dollars of brick and glass

enclosing

sumptuously decorated rooms and ball-rooms – all

empty. With no

gambling there were no tourists. The reports of the

turmoil in

Cuba had made many exchange their plane tickets for Puerto

Rico

[La

Concha Hotel - San Juan 1958]

[La

Concha Hotel - San Juan 1958]

Jamaica

[Arawak Hotel in Jamaica 1959]

and other nearby vacation areas. Others went to Las

Vegas where

the wheels still turned and the dice rolled merrily.

So Fidel Castro made an about-face, issued another

proclamation, and

bingo, gambling came back to Cuba. The little ball

whirled around

the roulette wheel again and the cards were

reshuffled. The

government hired advertising agencies to tell the glad

tidings in

newspapers and magazines. They issued pamphlets and

brochures to

be distributed to customers by travel agencies. The

tourists

returned.

When they again walked into the casino they saw many new

faces, many

old ones. The big-shot gangsters had been sent packing

and agents

of the government ran the show. It wasn't as good a

show as

previously, but the tourist could still win a little and

lose a lot.

As tourist activity stepped up, so did Castro's accusations

against the

United States. Communism reared its red head.

Turmoil

didn't abate. Scare headlines topped the front pages

of American

newspapers. Again, the flow of tourists dried to less

than a

trickle. It is estimated now that tourists are down to

ten

percent of their former numbers.

What turn gambling will take in Cuba under Castro is unknown

now.

Cubans have always distrusted a government connected with

gambling. They have seen dictators and revolutionary

strongmen

come and go, and when they have gone, the money has gone

also.

Even the change of the lotteries into "investment plans," in

which

tickets are bonds payable in five years as well as on weekly

winning

numbers, with the money used to build roads and public

housing, has not

reassured Cuban observers.

If Castro continues legalized gambling, government

corruption and the old-line criminals are expected by many

to creep back in.

If Castro again abolishes gambling, the government

investment of

millions in hotels and nightclubs and casinos will be lost

as will the

tourists.

For Castro, it's a losing bet either way.

End of Page

Copyright

1998-2014 Cuban Information Archives. All Rights

Reserved.

Top dog in the legitimate gambling racket in Cuba was

Santo (Louis Santos) Trafficante from Florida, the Einstein of the numbers game. Trafficante was given a full interest in the casino of the