CUBAN RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

OF AFRICAN ORIGIN

[GENTE

Magazine, Vol. 1, Havana, January 5, 1958, No. 1, American

Edition]

Page35

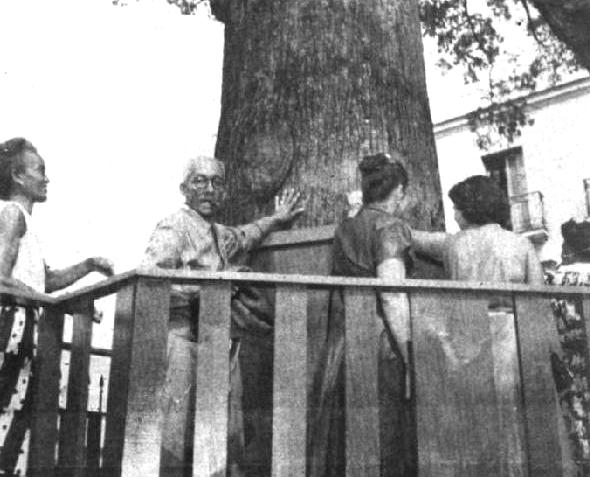

PHOTO CAPTION

- One

of Cuba's strongest African customs is that of visiting

the famed ceiba

tree at the Template on Saint Christopher's day.

This African

Custom is complied with by Havana residents on the

appointed date of

every year.

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS OF

AFRICAN ORIGIN

It is impossible to find in Cuba even a small segment of

art, custom

and tradition which does not contain a vestige of

Africa. The

integration of the country has been in progress for

centuries; the

contributions of the two races have been equally

vigorous. On the

one hand the Spanish blood, mixed with that of the Arabs and

the Moors;

on the other the African blood of former Negro slaves.

The

mixture of the two blood strains is evident in all

Cubans. The

following report will attempt to show as exactly as possible

the type

of culture in formation in Cuba today under the influences

of modern

civilization which play a large role in the nation's

development.

Suffice it to say that the religious customs and beliefs of

the

Afro-Cubans as practiced on the island today contain no

remnants of

cannibalism or witchcraft. The only "human sacrifice"

entailed is

the payment of "fees" as demanded by the Babalao. The

rites,

therefore, are as highly respected as any other religious

belief which

has developed over the centuries in peace and harmony with

the

Christian moral.

The photographs used to illustrate this report are forbidden

by the

laws of Santeria. GENTE has gone to great lengths

information and

entertainment.

VOCABULARY

Santería - The religious belief of the Negro Lucumis or

Yorubas

after their arrival in Cuba and other islands of the

Antilles group.

Changó - The god of war of the Lucumi belief, identified

with the Catholic's Saint Barbara; his color is red.

Ochosí - The god of the hunt, also representing justice.

Elegguá - The god of the highways. Elegguá is really

three gods in one– Echú, Laroyé and Elegguá.

Ochá - The name given to the African belief which preaches

goodness, or Santería.

Babalú - Ayé - A warrior god and a leper, who was

expelled from the land of the Yorubas and later reigned in

Congo

land. He is the brother of Changó and is identified

with

the Catholics' Saint Lazarus.

Yemayá - Goddess of the seas, owner and creator of the

world. Her color is blue. She was Changó's first

lover and in turn was his adopted mother.

Ebbó - The name for a practice in Santería whereby evil

influences are cast out of the worshipper's body and spirit.

Güije - A type of gnome who dwells under bridges in the

rivers. He is a mischievous and diabolic spirit.

A poe

describes Güijes as "dwarfs with enormous navels' and speaks

of

"their short and twisted legs their large straight

ears". The

Güije has the power of changing shapes and being ubiquitous.

Oggún - The god of iron, owner of arms and machinery.

A warrior, his color purple.

Babalao - The supreme priest of Santería. His name

means wise man. He is a protege of Orula.

Page 36

PHOTO CAPTION

- The

Santero put his question to the Snails of the Diloggun,

the scared book

which contains the answers to any question put to it by a

worshipper. The position of the snails when they

fall into place

provides the Santero with his answer.

Orula - The wizard owner of the divination board and

necklace.

Bembé - The great feast of Santería (described in text)

Ifá - The necklace used by Babalao for his divinations.

Ekuele - The divining board on which Babalao throws the

necklace of

Ifá, the position of the necklace indicating the answers to

questions put to it by the worshipers.

Aleph - God, the supreme creator.

Ilé - Home, domicile, residence.

Obatalá - Goddess of purity and representative of

Olofi.

She is "owner of all the heads" and the only one able to

communicate

directly with Olofi when he comes down "the road of Osán

Guiriñán". Obatalá is the equivalent of Our

Lady of Mercy.

Osán Guiriñán - A road known only to

Obatalá and leading to the "ilé" of Olofi atop an

inaccessible mountain.

Oyá - Goddess of cemeteries, identified with the Catholics'

Candelaria.

Aché - The gift and power granted by Aleph.

Agallú - Solá - The boatman appointed by Aleph, identified

with Saint Christopher.

Icú - Death, works for "Oyá" who presides over the

cemeteries.

Gangulero - A priest who practices evil, a witch.

Amalá - A food of cornflower and mutton and preferred by

Changó.

Iyalochá - Priest, or initiated woman, minor official of the

Lucumí religion.

Apesteví - The priest's helper, a kind of waitress who cares

for

the "prendas" or saints. Pure and chaste at the

outset, she later

becomes the concubine of the priest whom she assists.

Jícara - A typical Cuban cup made of a half-empty

güira. The güira is used in making "maracas".

Batas - Sacred drums used in the festivities. Their

name are Okonkoló, Iyá and Bata.

Since 1515, when the firs cargo of African slaves arrived in

Cuba, the

religious customs of the Negroes have played a large part in

the

beliefs or the Cuban people. The fusing of the

Christian ritual

of the Spaniards' and the pagan ritual of the primitive

people has

resulted in a true religious sincretism. Today the

mixture of

African fetishism and the refinements of Western religious

forms the

bread basis for a large segment of the Cuban people.

It is not strange, therefore, to meet an elegantly dressed

woman with

aristocratic bearing on t he streets of Havana and note

somewhere on

her person evidences of primitive beliefs known throughout

Cuba as

"santeria". You may see among her gold jewelry and

adornments

–pure gold pins and decorations are not uncommon in Cuba

today– a

golden sword, a bow and arrow or a bracelet of knitted

leather with a

core of gold or coral. You may notice that she is

wearing seven

bracelets, or that she has a small chain on her ankle. All

are symbols

of beliey [belief] in some African god...

The "Sons of Changó" exhibit their war sword on their chests

and

their lapels. The "Sons of Ochosí" display the bow an

arrow. Bracelets are the symbol of Ochún the Venus of

those of the Lucumí sect.

If you visit a Cuban home you may not see any inmmediate

[immediate]

indications of santeria beliefs. But perhaps you will

later note

a small cabinet behind the door. This is the "home" of

Elegguá, in African credo the custodian of roads and

highways

and who, according to the laws of Ochoa, is trusted with the

safety of

the home. Behind the door you may also find the

"bread" of

Babalú Ayé. You may also notice a duck which is

permitted complete freedom in the house. Or you may

notice that

the dog of the house is treated as

Page 37

PHOTO

CAPTION - Santero

Felipe

Montes de Oca demonstrates a devil fish while in the

background

can be seen the "canastillero" where the saints

live. On top of

the "canastillero" are visible the African "Orishas", or

symbols of

Catholic saints, mainly the "Caridad del Cobre", showing

the mixture of

African and Catholic religious figures.

ADVERTISEMENT

- Hotel Copacabana

though he were the owner instead, and all because it is so

decreed by Babalú.

Sometimes, at high noon as you walk through the neighborhood

streets,

you will see someone throw a bucket of water out on the

sidewalk, or a

woman will intentionally drop a bottle of clear, clean water

in the

middle of the streets...

And then at dawn some day you will find the "refuse of Ebbó"

or

at street corners. It was left there by believers to

drive away

the evil spirits...And if you pass under two crossed palm

leaves, you

may find on the ground nearby apples, bananas and red

handkerchiefs

–all dear to the warrior Changó de Imá...

And in the country there are still Cubans who will not

whistle inside

empty houses because it serves to summon the "güijes".

And

there are also those who, before stitching a piece of

clothing worn by

another person, will prick the wearer slightly to prevent

the god

Ogún from forcing a slip of the needle. And there are

still people who prick their fingers with a new

Page 38

ADVERTISEMENT

- El Carmelo Restaurants and Stores

knife before using it for the first time.

Until very recently believers in these truely [truly]

African customs

offered a "bembé" to Ogún in the sugar mill before

starting the refining process. And a dark-colored dog

was placed

on the railroad tracks to appease the god who presides over

iron,

machinery and armaments and thus prevent serious accidents

during the

milling.

All of these practices are "trabajos" and are santeria

ritual.

They are explained by the racial integration of Cuba where

Negro

traditions and beliefs, brought from Africa, has fused with

those of

the Spanish "conquistadores".

Cuba today is full of santeria beliefs as well as persons

who,

unknowingly perhaps, still carry on traditions passed on

from their

grandfathers and which had their origins in the jungles and

flat lands

of Africa.

The true believer who visits the "babalao" places his faith

and hope in

the rites conducted by the pagan priest. The latter

recites and

esoteric dialogue between the gods while the necklace of Ifá

is

thrown on he Ekuele board by an unseen hand. The

believer knows

that the "registro" or advice which he receives from babalao

is the

true word of God, for babalao, which means "wise man", knows

all.

Babalao is the representative of Orula, the god to whom

Aleph, the

Supreme Creator, entrusted the divining board when it was

abandoned by

undisciplined Changó.

And because its law is the law of God, the believer does not

hesitate

to heed and obey its commands, regardless of the effort or

consequences

it may entail.

HUMAN ASPECTS OF THE GODS

One must understand that primitive peoples select their gods

from among

their better known neighbors. Legend tells us, for

instance, that

Aleph, weary of ruling the world with its endless problems,

decided to

divide his powers among the saints of the Lucumí pantheon

and

retire to an isolated and inaccessible hilltop, to the top

of which

only Obatalá and the mischievous Eleguá knew the route.

So Aleph gathered around him the saints and explained his

decision. He called forth Yemayá and placed all the

seas

in her lap. Then Saramagua shook her skirt and

separated the

oceans and the continents, giving the world the

configuration that is

has today. To Changó, Olifí gave the lightning, the

thunder and the thunderbolts; to Ochún he gave the rivers

and

the honey and the waters of the sweetest springs; to Ogún he

gave the iron; to Elegguá he gave the roads and highways;

and to

Oyá he gave the cemeteries. And so it went.

Each of the gods thus sanctified retained his particular

characteristics.

Page 39

PHOTO CAPTION

- The

Santero officiates before the "canastillero" in which the

African gods

dwell. Here the practices of Santeria are

conducted. This

is the room of the saints. Seen on top are Obatalá,

Ochosí and Ochún. In the center are Yemayá

and Changó, and underneath Ogún and Oyá. On

the floor are the Obeyes or twins.

Ochún continued to be lascivious; Yemayá, maternal;

Obatalá, austere and pure; Changó, mischievous, fickle,

voluble and astute; Ochosí; Agallu Sola, rigid and severe.

Thus the African saints retained all the humans traits, both

good and

bad. And that is why they love, hate, envy, argue,

fight and,

despite the fact that they are gods, that they are

occasionally

deceived by those who believe in them.

"CHANGING THE HEAD"

When a persons is seriously ill and Icú, the god of death,

demands their life, the santero or priest of voodoo is

permitted to

"change the head".

This ritual consists of offering up prayers in the wizard's

room in

which the priest officiates at his mystic ceremonies.

The prayers

result in the transfer of the illness from the sick person

to another

person, be he healthy or sick. And if this other

person

does not, in the same manner, have the sickness transferred

to still

another person, he will surely die.

The wizard explains the ritual thusly, that Icú demands a

dead

body and that his desire must be granted; and that as it is

immaterial

what body be given up to the god of death, the body of

another will

serve the purpose as well.

And this is the ritual which is called "changing the

head".

Crying for the Sic Person

Unfortunately there are times when it is next to impossible

to convince

Icú that another body will serve as a worthy substitute for

that

of the sick man over whom the priest is praying.

Then the work cut out for the priest is more

difficult. He must apply stronger and more dramatic

measures. So a

Page 40

PHOTO CAPTION

- A head of

roughly-carved stone of singular primitive beauty

represents the god

Elegguá dwells in the pan of clay in which are embedded

the 21

snails which represent "the roads" of the god. It

is identified

with the Catholics' Baptist. In many Cubans houses

Elegguá

is found behind the door for protection of the home.

close relative of the patient, usually his mother or his

wife, will

dress a puppet made by the wizard in some of the sick man's

clothes. The puppet will then be taken to a cemetery

at midnight

and buried. Then the mourner will weep by the tomb so

disconsolately that Icú will be convinced that the sick man

has

in fact died.

Sometimes these extreme measures are not necessary.

Powdered egg

shell or some coloring may be applied to the sick's man face

and will

so disguise him that Icú will believe him already had

died...

The same practice is also used to deceives enemies when they

try to inflict serious injury on a person.

THE FOOD OF THE SAINTS

Before the altars of their gods, believers place their

deities'

favorite dishes. For Ochún there are fried green

bananas;

to Obatalá they serve popped corn; for Changó there is

"Amala" and bananas, while tobacco and brandy are served to

the

demanding warrior gods...

Sumptuous banquets are served, however, on the occasion of

large-scale

celebration in honor of the gods, Babalao officiates at

these feasts,

assisted by Iyalocha, the Apestevi and their "godchildren".

Animals are slaughtered for the feast in large quantities

and in each

case the rigid laws of the beliefs are scrupulously

observed.

Babalao is the only god to whom four-legged animals can be

sacrificed,

for example. Bipeds may be sacrificed to the Santera,

or

Iyalocha. But each rite demands the attedance

[attendance] of the

worshipper who is preparing the feast. All sacrifices

must be

made in his presence. Each piece of the quartered

animal is

placed in front of him after he has been touched on the

head, palms,

knees and ankles with the dead flesh.

While this is being done the worshipper invokes the gods and

makes the offering in the Lucumí tongue.

The blood of the animals is collected in "jícaras" or in

porcelain cups, mean while, and is offered later to such

gods as

Oggún, who usually demands it.

THE BEMBÉ

The main ceremony of Santeria is the Bembé or "toque de

Santos"

as it is also known. The rite both begins and ends

with prays to

Elegguá

The ceremony resounds to the sound of the "atabales".

The "batas"

drums beat incessantly. The "güiros" provide further

background for the choir of voices which raises its chant to

the

dwelling place of the "orishas". The faces of the

worshipers seem

transformed by the esoteric summons to possession. The

gong of

the atabales sounds louder. The odor of the jungle

invades the

place of worship. The chant grows louder on the Lucumí

tongue:

"Ilá mi ilé oro...

"Ilá mi ilé oro...

"Iyá mi.

"Iyá mi, Saramawooooo

"Iyá mi ilé oro...

The sweating bodies shake in a frenzy with each beat of the

drums. Legs, shoulders and bodies tremble as if

reacting to an

electric shock. A strange feeling of well-being

invades every

heart; it is visible in he emotion-twisted faces and the

bleary eyes of

the dancers. Their temples pound. At last

–a body

becomes possessed. A woman falls to the floor, her

body jumping

savagely, while from hundreds of throats the cry resounds.

"Gecua, Gey..."

This signifies the arrival of the saint. He has

entered the body

of a believer. He is among them and preparing to speak

with the

tongue of his "horse" and to dance in the physical form of

his

"instrument".

If you were to ask the santero what happening, he would tell

you that

Page 41

ADVERTISEMENT

- Gran Hotel de Santa Clara

the saint has displaced the soul of the worshipper and

occupied his

body, to be able to communicate with men here on

earth. The

saint, he would tell you, is of spirit and space and lacks

the physical

attributes of a human...

Now the saint dances frenetically to the beat of the drums

which incite him to further frenzied motion.

The Bembé has entered its moments of climax. Now

everything is jungle –primitive, vigorous, fringed with

omens and deep

fears...

Before "departing", the god will speak to the men, will

advise hem on

ways to preserve their health, to avoid "troubles", to help

others find

employment. The god will also ask his due; he will

demand a feat;

he will even threaten his naughty "children".

And when the saint has left the body of the "aleyo", faith

and belief

will be stronger, and the body of the possessed will be sore

in the

aftermath of its frenzied contortions.

These are the origins of the diverse African belief still

found in

Cuba. They are everywhere on the island. A

traces of

Africanism remains in every Cuban, giving rise to a popular

tune which

goes:

"He who does not wear yellow (the color of Ochún).

"Covers himself with blue cloth (the color of Yemayá).

"Or red (belonging to Changó)".

That is also the thought behind the proverb: "There are

those who remember Saint Barbara when it thunders".

For the same reason a politician once noted that "in Cuba

the man who

does not have an ancestor from the Congo has one from

Carabalí..."

Article by columnist:

FELIPE ELOSEGUI

End of Page

Copyright

1998-2014 Cuban Information Archives. All Rights

Reserved.